Abstract

Background:

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is second in importance to smoking cessation treatment in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Access to the service is limited and less than half of those referred complete the treatment.

Aims:

We assessed the obstacles to participation in PR among COPD patients in a community-based PR programme and associated general practices.

Methods:

A qualitative interview study was conducted among COPD patients who completed the PR treatment, those who did not complete or declined treatment, and patients never referred. Participants were invited by letter from their own general practitioners or from the PR service. Views on exercise, disease education, social contact, group activity, accessibility, location, role of referrer, and support for participation were assessed. Data were analysed using the framework approach.

Results:

Twenty-four patients (28%, 13 male, 12 not referred) were interviewed. The acceptability of PR was the major concern. Feasibility of attending was an issue for some. Perceptions of PR and of exercise were highlighted. How a smoker might be seen, the suitability of group activity, and the views of professionals were influential, as were positive and negative recommendations. The location of the centre was important. Participants’ willingness or reluctance to take on something new was a central element of the decision. Many would welcome the role of experienced patients in introducing the treatment.

Conclusions:

For patients who refused referral to PR, had not completed a course, or had yet to be referred, the way the service was introduced was an important determinant of willingness to participate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) should be the mainstay of treatment after smoking cessation in all grades of symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).1–3 It relieves symptoms, improves quality of life, and increases exercise capacity.2,4 It is more effective in these domains over periods up to 6 months than long-acting inhaled bronchodilators and combination inhaled long-acting bronchodilators and corticosteroids, and a recent trial has shown a substantial reduction in the risk of readmission in patients who undertake PR immediately after admissions for COPD.5–8 Its effectiveness is not preserved over time, however, and strategies for maximising its sustainability are required.9,10 For most people with COPD whose treatment is largely managed in primary care, access to PR is likely to be controlled by the primary care team. Factors that influence referral and uptake of PR for COPD patients are therefore of considerable importance in that setting.

Significant drop-out rates or non-completion have been observed in 26 clinical trials of PR in which up to 75% of participants were non-completers due to ineligibility or drop-out.11 Celli et al. in the USA found that 53% either declined to take part or dropped out.12 There is poor understanding of the barriers to and effective facilitators of this treatment. Research among potential participants who have refused referral suggests that exercise was not perceived as a worthwhile treatment or that difficulty getting to the programme, the burden of COPD itself, and commitment to other competing activities were factors in preventing participation.13,14 Keating et al., in a recent systematic review, found that obstacles to initial uptake were unevenly described and included disruption to valued routine, uncertainty of the referrer in its effectiveness, inconvenient timing, travel issues, and low perceived benefit.15 Knowledge of the cause of drop-out was also limited and included illness and co-morbidities, travel, current smoking, lack of social support, COPD exacerbations, and low perceived benefit.15 Severe disease was associated with dropout in the UK and the USA, and Garrod et al. in the UK found that quadriceps weakness and depression were also predictors of drop-out.16–18 Among patients who have not been referred, fear of exercise and breathlessness in PR has been reported.19 If this treatment is to be taken up by the majority of COPD patients, a more precise understanding of the factors that promote and prevent participation in PR is required.

In this paper we report on the feasibility and acceptability of PR in patients who completed the treatment, patients who did not complete treatment, patients who were referred but did not take part, and patients with COPD in primary care who were never referred for treatment.

Methods

A cross-sectional qualitative interview survey was conducted in COPD patients recruited in south-east London between January and April 2009. The aim was to assess the acceptability and feasibility of community PR in patients in primary care. Feasibility was defined as the ability or capacity of patients to attend PR. Acceptability was defined as their willingness to attend. Ethical approval was obtained from Guy's Hospital Research Ethics Committee (ref no 08/H0804/164) and King's College Hospital Research Ethics Committee (ref no R&D: KCH823). Research governance approval was obtained from the Research and Development Centre for Primary, Community and Social Care at Southwark PCT (ref no DRLS 450).

The study was carried out and this paper was written with reference to the COREQ criteria for reporting qualitative studies.20 The theory underlying this research was based on the framework approach because it followed specific and limited questions informed by previous research, and therefore adopted a more deductive approach to the analysis.21,22

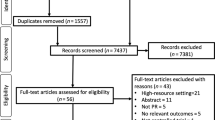

Eligible patients included those who had attended a course of PR (completed or not completed), those who had been referred to the service but had not attended, and COPD patients who had not yet been referred. Random sampling was chosen as the method of participant selection within each of these three groups because evidence from earlier studies suggested that most of the variance in uptake and completion of PR was not explained by demographic characteristics such as age, gender, or socioeconomic deprivation.15–19 The role of disease severity remained an open question at the time of the study, so the random sample was stratified by severity in PR-naive patients and by experience of PR in those previously referred. A random sample was obtained in each setting and patients were recruited until at least 24 had been interviewed or data saturation had been achieved. Data saturation was difficult to gauge because there were three distinct groups of participants. If data from one of these groups had turned out to be distinct and to raise themes not encountered in the other groups, provision was made to enable further recruitment in that group. Patients with a diagnosis of COPD who were not previously referred to PR (described as ‘not referred’ in the results) were identified from the lists of four general practices. Eligible patients who had not been referred previously to PR had to have a confirmed diagnosis of moderate or severe COPD (forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) <70% predicted and FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) <0.7). We aimed to recruit 12 COPD patients who had not previously been referred to PR and 12 patients who had been referred. Patients who had been referred previously to PR in Lambeth or Southwark Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) between January and December 2008 were identified from the treatment register of the community PR service and invited for interview. Patients who were illiterate, who were unable to read or write English, those who had a mental illness such as dementia or a terminal illness were excluded.

Patients were invited to take part in the study by letter from their GP or from the PR service. Those who expressed interest were telephoned by one of the authors (LM) and invited to undertake an interview in their homes or in their GP's practice. Informed consent was obtained. Patients were allowed to have a supporter at the interview. No repeat interviews were carried out. LM had previously received training in qualitative interviewing.

Interviews were semi-structured and used a topic guide which was developed by LM and PW based on previously published research and after consultation with a PR specialist (LH). The interview schedule was piloted by LM with two patients at a PR treatment session. The topic guide included the following headings: understanding of COPD; understanding of PR and views about attendance before and after a detailed explanation; views about exercise, disease education, social contact with fellow sufferers, and participation in group activity; accessibility; location; role of the referrer; and support for participation including attitudes to the role of experienced patients (lay health workers).23 The interview schedule is shown in Appendix 1 available online at www.thepcrj.org. No patient was known to LM prior to interview. Participants completed the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire self-report version (CRQ-SR) to enable comparison with all patients who attended the PR service.24 The interviews were all carried out by LM and lasted on average 1 hour. They were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were entered into NVivo 8 (QSR International (UK) Ltd, Southport, UK). Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment.

Analysis of data

A coding framework was derived initially from the topic guide and amended in response to the interview data. The transcripts and data extracts were read independently by LM and PW who conducted a separate thematic analysis. Consensus was reached on the definition and organisation of themes and the choice of data to be reported in the paper. Themes were compared and contrasted using the framework approach.21 Data were processed in line with the key themes using familiarisation, identifying a framework, indexing, charting, and interpretation. We have limited the presentation of themes to the major themes and have not included description of diverse cases although evidence of some of these can be seen in the data presented. The data are presented to illustrate the themes identified and are annotated with the sex, age, category of participant, and order in which the interview was conducted.

Results

Twenty-four (28%) of 85 COPD participants were interviewed (14 male and 10 female, average age 68 years, range 47–84), all with FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7 and percent predicted FEV1 <70%. Fourteen lived in rented accommodation, nine were in owner-occupied accommodation, and one declined to reveal housing circumstances. Eleven participants lived alone. None were housebound. Eighteen were white British, three were white Irish, two were black Caribbean, and one was white and black Caribbean. Eighteen were retired, three were unemployed, two were in employment, and one was on long-term sick leave. Twelve were recruited from the community PR treatment register of patients (2007–2008). Seven of these had completed PR of whom three had initially declined the treatment, four had not completed PR of whom one had initially declined, and one had declined attending PR and never attended. Twelve COPD participants not known to have been referred to PR were recruited at four general practices. The mean scores in the CRQ-SR (range 0–7, least disability=7) were: dyspnoea: 2.4 (range 1.6–3.8), emotion: 4.9 (range 2.7–6.9), fatigue: 4.0 (range 1.5–6.25), and mastery: 5.1 (range 2.75–7.0). These scores did not differ in severity from mean scores in the service associated with this study. The decision whether or not to undertake PR was complex for study participants. It has been analysed in terms of feasibility (influenced mainly by co-morbidities and carer responsibility), and in terms of acceptability. The distribution of themes of obstacles to or concerns about participation is shown in Table 1.

Feasibility

The ability or capacity to attend PR was an issue for four participants in this study. Two participants were unable to attend the PR programme due to co-morbidities and two due to carer responsibility (Box 1).

Acceptability

The acceptability or willingness to attend PR was the main area of analysis. All who had attended PR had a positive perception of its suitability and would recommend it to others. In considering obstacles to taking part, analysis generated the following themes: expectations and preparatory information including the role of experienced patients (lay health workers); difficulties with access due to geographical boundaries or timing; difficulties in prioritising the treatment; contrary beliefs about the role and safety of exercise; fears about criticism, exposure and inadequacy.

Expectations and preparatory information

Participants reported differences between their expectations and the reality of the experience when they started the treatment (Box 2). The fact that PR sessions incorporated an educational component was not often understood by those who had not attended PR.

For some participants the referral to PR from the nurse or doctor was sufficient. For others the experience of an exacerbation just prior to the referral was a key element of finding PR acceptable. Some participants were unwilling to attend PR because of the lack of information about it. They would not attend unless the about the information about the service was presented in a suitable way.

There were both positive and negative responses to the suggestion that referral to PR might be accompanied by the attendance at the sessions of an experienced patient who had previously completed a course in PR (lay health worker). Nearly half the participants were of the opinion that it would be useful if a patient who had previously completed a course in PR had contacted them when the referral offer was made (Box 2).

Difficulties with access due to geography or timing

Location was cited by several participants as the reason for refusal to attend PR (Box 3). Some did not know the area in which the services were provided, some thought the distance was too far, and some mistakenly thought that the services were only provided at the hospital. Timing was important for some who were worried that they may not cope with an early start. The length, complexity, and familiarity of the journey to PR were also a concern. The time of year in which a session might be held was not a concern as long as the particular day was not too hot or too cold. Although a few of the participants could not attend during working hours, the most common preference with respect to timing was that the PR sessions should not start before 9.30 and preferably not before 10.00. A number of participants preferred not to attend at the weekend.

Difficulties in prioritising the treatment

Some refused to attend because they did not consider PR a priority in their lives or because they did not feel their condition was at a level that needed PR (Box 4).

Contrary beliefs about the role and safety of exercise

Several subjects were able but reluctant to attend PR due to negative perceptions of the role of exercise, either because it would not be useful or it might be harmful (Box 5). Participants who were willing to or had attended PR recognised the need for more exercise, the usefulness of routine attendance, and the support of professionals with the exercises.

Fears about criticism exposure and inadequacy

Fears were expressed about being unable to cope with exercise or being too disabled to take part (Box 5). One participant did not like the prospect of undertaking the treatment in a group. A smoker expected criticism of her smoking at PR and thought that if she gave up smoking anyway the need to attend would be eliminated. These fears were countered by the experience of those who had undertaken PR which was that the treatment was highly supportive (Box 5).

Themes presented here were reported by at least one participant from each of the four categories of participants. We were not able to detect a difference between categories of participants in the dominance of particular themes, with the exception of perceptions of the acceptability and effectiveness of PR in participants who had undergone the treatment.

Discussion

Main findings

The acceptability of PR was the major concern of participants in this study. Feasibility of attending PR was not an obstacle for most participants. Views of the acceptability of PR in terms of reasons for taking part or not, being concerned about participating, and deciding whether or not to participate were expressed in themes shared by participants who had never been referred for PR, those who had been referred and chose not to take part, and those who did undergo PR. For some participants the very reasons for joining PR were the same reasons others gave for not wanting to take part. Our findings highlight the importance of understanding the preconceptions and expectations of patients who would be suitable for referral, and the potential for overcoming the barriers that currently lead to the unacceptably low uptake and completion of PR by patients with COPD.

The general perception of PR and the role of exercise in the treatment of COPD were significant issues. More specific perceptions of the priority of rehabilitation and exercise, the way a smoker might be seen in the setting of PR, the suitability of group activity, and the views of professionals with whom participants had contact were influential in determining or reflecting positive and negative perceptions of PR. Positive and negative recommendations by neighbours, family and friends were reported to be persuasive. The decision to refer and the referral process, together with the information provided about the service at the time of referral, were reported as significant. The location of the PR centre — for example, in hospital or in the community — was a factor that supported and impeded participation. Finally, participants' willingness or reluctance to take on something new appeared to be an important element in the decision to take part.

Strengths and limitations of the study

One of the strengths of this study is the inclusion of the views of patients not yet referred who are among the patients for whom PR will be the definitive treatment in the future should they be referred and take up the offer. Understanding the range of their perceptions and expectations will make a significant contribution to the development of an intervention to improve uptake.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

Published evidence up to this point has either used routinely collected data or has analysed data as part of the analysis of outcome of a service.15,16,18,25 Views of participants who had not been groomed by prior information about PR are important contributors to the range of views about the feasibility and acceptability of PR to COPD patients. Themes identified in this research as obstacles to participation in PR not previously identified in the systematic review of Keating et al. include the role of experienced patients (lay health workers), difficulties in prioritising the treatment, contrary beliefs about the role and safety of exercise, and fears about criticism, exposure and inadequacy.15,23 One of the underlying themes behind fears of criticism and a feeling of unworthiness may lie in the sense of stigmatisation of COPD sufferers and the feelings of self-blame and disgrace described by Halding et al.26 Such stigmatisation becomes more powerfully experienced in interactions with strangers and may augment resistance to participation in PR.27 Other patients with COPD are likely to have such an acceptance of their disease and the slowly changing state of their health that they may not expect therapeutic interventions such as PR to offer hope of symptom improvement.28

Implications for future research, policy and practice

The uncovering of new understanding on the acceptability of PR may only have been possible with a qualitative study. It is therefore a crucial stage in the strategy to understand and transform low participation in what is the most effective treatment in improving the quality of life of these patients.2 The responses described here will inform the development of experimental interventions towards a formal trial to improve dissemination of PR to the majority of patients with COPD who are currently not receiving the treatment. One potential intervention well received by participants here was the proposed use of experienced patients, sometimes called lay health workers.23

Of the themes identified, ‘feasibility’ was the least amenable to intervention. Knowing the proportion of COPD patients for whom PR is not feasible will aid the development of home-based services for this group (including home-based DVD and home-based exercise programmes).29,30 The ‘acceptability’ of PR to patients is the area in which further exploration and experimentation is required. This should include the definition of the proportion of patients who are referred but choose not to attend and the reason for the non-attendance; more detailed analysis of the referral itself; the role of information provision; and how expert patients might be used.

Conclusions

It is clear from this research that, for patients who have refused referral to PR or have not completed a course and for some of those yet to be referred, the way the service is introduced and explained and the capacity of the service to fit their lifestyle requirements are likely to be important determinants of their willingness to undertake the treatment. The extent to which these observations are reflected in the population of COPD patients as a whole needs to be investigated. Service commissioners should highlight the need for further research to clarify improved methods of introduction and referral to PR and the possible use of lay health workers in supporting newly referred patients. Interventions to improve the uptake of PR by those who are currently negatively disposed are urgently required if PR is to achieve the improvements in the outcome of COPD treatment which have been demonstrated in clinical trials.

References

National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010, p.1–673.

Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S . Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(4):CD003793.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (updated 2009). 2009.

Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2007;131(5 Suppl):4S–42S. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-2418

Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356(8):775–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa063070

Wedzicha JA, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, Hagan G, Ansari Z, Stockley RA . The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177(1):19–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200707-973OC

Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359(15):1543–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0805800

Seymour JM, Moore L, Jolley CJ, et al. Outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation following acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax 2010;65(5):423–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.124164

Cockram J, Cecins N, Jenkins S . Maintaining exercise capacity and quality of life following pulmonary rehabilitation. Respirology 2006;11(1):98–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00791.x

Griffiths TL, Burr ML, Campbell IA, et al. Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355(9201):362–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07042-7

Bjoernshave B, Korsgaard J, Nielsen CV . Does pulmonary rehabilitation work in clinical practice? A review on selection and dropout in randomized controlled trials on pulmonary rehabilitation. Clin Epidemiol 2010;2:73–83.

Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350(10):1005–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021322

Fischer MJ, Scharloo M, Abbink JJ, et al. Drop-out and attendance in pulmonary rehabilitation: the role of clinical and psychosocial variables. Respir Med 2009;103(10):1564–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.020

Keating A, Lee AL, Holland AE . Lack of perceived benefit and inadequate transport influence uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. J Physiother 2011;57(3):183–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70040-6

Keating A, Lee A, Holland AE . What prevents people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from attending pulmonary rehabilitation? A systematic review. Chron Respir Dis 2011;8(2):89–99.

Sabit R, Griffiths TL, Watkins AJ, et al. Predictors of poor attendance at an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programme. Respir Med 2008;102(6):819–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.019

Cote CG, Celli BR . Pulmonary rehabilitation and the BODE index in COPD. Eur Respir J 2005;26(4):630–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00045505

Garrod R, Marshall J, Barley E, Jones PW . Predictors of success and failure in pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir J 2006;27(4):788–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00130605

Harris D, Hayter M, Allender S . Improving the uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: qualitative study of experiences and attitudes. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58(555):703–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08X342363

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19(6):349–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Ritchie J, Spencer L . Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, eds. Analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge, 1994. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203413081_chapter_9

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N . Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320(7227):114–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(3):CD004015.

Williams JE, Singh SJ, Sewell L, Morgan MD . Health status measurement: sensitivity of the self-reported Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ-SR) in pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax 2003;58(6):515–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thorax.58.6.515

Garrod R, Ford K, Daly C, Hoareau C, Howard M, Simmonds C . Pulmonary rehabilitation: analysis of a clinical service. Physiother Res Int 2004;9(3):111–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pri.311

Halding AG, Heggdal K, Wahl A . Experiences of self-blame and stigmatisation for self-infliction among individuals living with COPD. Scand J Caring Sci 2011;25(1):100–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00796.x

Berger BE, Kapella MC, Larson JL . The experience of stigma in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. West J Nurs Res 2011;33(7):916–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0193945910384602

Pinnock H, Kendall M, Murray SA, et al. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2011;342:d142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d142

McFarland C, Willson D, Sloan J, Coultas D . A randomized trial comparing two types of in-home rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2012;35(3):132–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/JPT.0b013e31824145f5

Thomas MJ, Simpson J, Riley R, Grant E . The impact of home-based physiotherapy interventions on breathlessness during activities of daily living in severe COPD: a systematic review. Physiotherapy2010;96(2):108–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2009.09.006

Acknowledgements

Handling editor Maureen George

Funding LM undertook this work as a research fellow seconded by Southwark Primary Care Trust to the Department of General Practice and Primary Care at King's College London. The research fellowship was funded by Guy's and St Thomas’ Charity through the Primary and Community Care Research Support Programme. She now works in the Clinical Governance Department of Guy's and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust.

We are grateful to the general practices who gave us access to their COPD patients who participated in the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by PW and designed by LM and PW with input from LH. Interviews were carried out by LM. Analysis of the interviews was carried out by LM and PW. The paper was written by LM, PW and LH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Appendix 1. Interview schedule

Appendix 1. Interview schedule

The acceptability and feasibility of community-based pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD patients managed in a primary care setting

Outline Interview Topic Guide — patients who have attended PR

Introduction

Interviewer:

1. Introduces herself 2. Checks pt's name 3. Checks pt understands reason broadly for visit — looking at support sessions for pts with breathing difficulties

4. Agreement from pt — well enough for visit today

5. Check's patient's Name......... Date of birth..........

6. More detailed introduction of study — Researcher working through the pulmonary rehab team and King's College London Uni meeting pts. Try & get a better understanding of why pts with breathing difficulties when invited to come to some sessions that would help them don't come — able/willing. I am referring to the pulmonary rehab or PR sessions that I understand you have attended.

6.1 Is that correct that you have attended some of these sessions in the past?

So PR is a number of sessions (usually around 8 to 10) of exercise treatment, talks by health professionals and an opportunity to meet others with a similar condition. This research study aims to establish the obstacles that prevent patients from taking part in these sessions or make them difficult to attend. I will be asking you your opinions on what these obstacles might be. There aren't any right or wrong answers. I am trying to gather opinions & experiences. I am asking a number of patients similar questions. This is the first part of the study. Your answers will help us decide what questions to ask in the second part of the study. The second part of the study is the completion of a questionnaire to over 600 hundred patients in the area with COPD as to what the obstacles are. There will be opportunity for you to pick up on anything at the end of the interview. I can't give you any clinical advice. I don't have a direct link with your clinical care.

7. Explains stages of the interview

You will have received a leaflet explaining the study. I have a copy here which you are welcome to have another look at. I'll make some notes & the interview will be recorded so that I don't forget things. I'll be using this guide to ensure we have gone through the main points. Before I leave I'll take you through a short questionnaire that will ask a bit more in detail how you are affected by your chest condition. Thank-you for agreeing to take part. It is much appreciated. Before I turn on the recorder I need you to sign this consent form which will give permission for me to ask you some questions. (Informed consent and turn on the recorder)

8. Establish the patients basic knowledge of their condition

8.1 I understand that you suffer from a condition called COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Is that a name that means anything to you?

8.2 What is the name you use for your chest trouble? Use the patients term

COPD is a name that covers the two conditions chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Is that correct that you have COPD?

8.3 What does COPD (or whatever they think it is) mean to you?

8.4 What impact does it have on you (nature of disease)?

8.5 How long would you say that you have had COPD (or the condition they describe)?

9. General — PR

9.1 Do you recall who was the first person to mention PR to you?

9.2 What did you think before you came along to the sessions that (pulmonary rehab) (rehabilitation) PR was?

9.3 When you first heard about PR was it called PR or pulmonary rehab or pulmonary rehabilitation? How did you feel about those terms? (understandable, scary) What do you think about the term “Better breathing for life”?

9.4 What sounded good about PR?

9.5 What sounded not so good about PR?

9.6 What made you willing (accept) going to PR session?

9.7 Did you have any doubts? If so what were the doubts?

9.8 Having gone through the PR programme would you be happy to do it again if the opportunity arose?

9.9 Did you have to make any special plans to be able to go to the PR sessions?

10. Information and knowledge of PR

10.1 Who first described PR to you?

10.2 How was it described to you?

10.3 Would the explanation of PR as a number of sessions (usually around 8 to 10) of exercise treatment and talks by health professionals which also provides an opportunity to meet others with a similar condition have been enough of a description of the sessions for you to decide whether you want to go to them or not?

10.4 We know from research that PR helps most people with your condition by improving their ability to take exercise, improving the quality of their lives, and improving their sense of control over the condition. Did you know this before you went to PR?

10.5 Would knowledge of what PR can do have made a difference to your decision to go along to PR?

11. Attitude to PR

Exercise, Talks, Socialising with others

I've mentioned the different elements of PR in terms of exercise treatment, talks by health professionals and an opportunity to meet others with a similar condition — so looking at them in a bit more detail. Let's start with exercise.

11.1 How did you feel before you went to PR about exercising at a PR session? (Prompt — worries)

11.5 How did you feel before you went to PR session about being given talks?

11.9 What had been your experience of meeting others who have similar health condition before PR?

12. Activities in groups

12.1 How did you feel about being part of a group of people?

13. Accessibility and location -

13.1 Was the location acceptable to you?

13.5 Did it matter to you what time of year the sessions were held in i.e. winter/spring/summer/autumn?

13.6 Did it matter to you what time of the day the sessions were held?

13.7 Would it matter to you if the sessions were once a week over a longer time period or more frequently over a short time period?

14. Who refers

14.1 Would it matter to you which professional e.g. doctor/nurse recommended you to go to PR? Why do you think that is?

14.2 Would you have known about PR without a doctor or nurse mentioning it?

15. Support

15.1 Do you think if you had the opportunity to have someone with COPD with experience of the sessions contact you when you were invited for PR that would be useful in making a deicion whether to attend or not?

15.2 Would it be helpful to have someone with COPD who has been to PR sessions themselves at a session with you?

16. Other obstacles

16.1 Are there any other things that would stop you going to PR?( Prompt — lack of time, competing activities, responsibilities, other medical conditions that limit ability to take part)

16.2 Smoking. It's accepted that COPD is a condition that affects people that have smoked and we all know how difficult it is to give up something we enjoy doing. Some work has been done that shows smokers are less likely to attend PR than non-smokers so we really to need understand this point. So do you smoke? If Yes, did that make you think twice about going to PR?

Why was this?

17. Other comments —

17. 1 Are there any other points or comments relating to PR that you wish to mention?

Check patients demographic details from sheet — marital status; living with anybody

18. Many questions

18.1 We have covered a lot of things today, thank-you. Your answers are valuable to me as they will enable me to set the important questions in the survey that I will be sending on a form to a large amount of patients. Have there been any questions that I have asked today that would have stopped you completing a form?

MRC dyspnoea scale??

QOL questionnaire

Demographic form

Thank-you to the participant & offer to present a summary of the research

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, L., Hogg, L. & White, P. Acceptability and feasibility of pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD: a community qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 21, 419–424 (2012). https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00086

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4104/pcrj.2012.00086

This article is cited by

-

The IMPROVE trial: study protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of using lay health workers to improve uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Trials (2024)

-

Understanding patient participation behaviour in studies of COPD support programmes such as pulmonary rehabilitation and self-management: a qualitative synthesis with application of theory

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2015)

-

A Review of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Panic Disorder in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The Rationale for Interoceptive Exposure

Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings (2014)